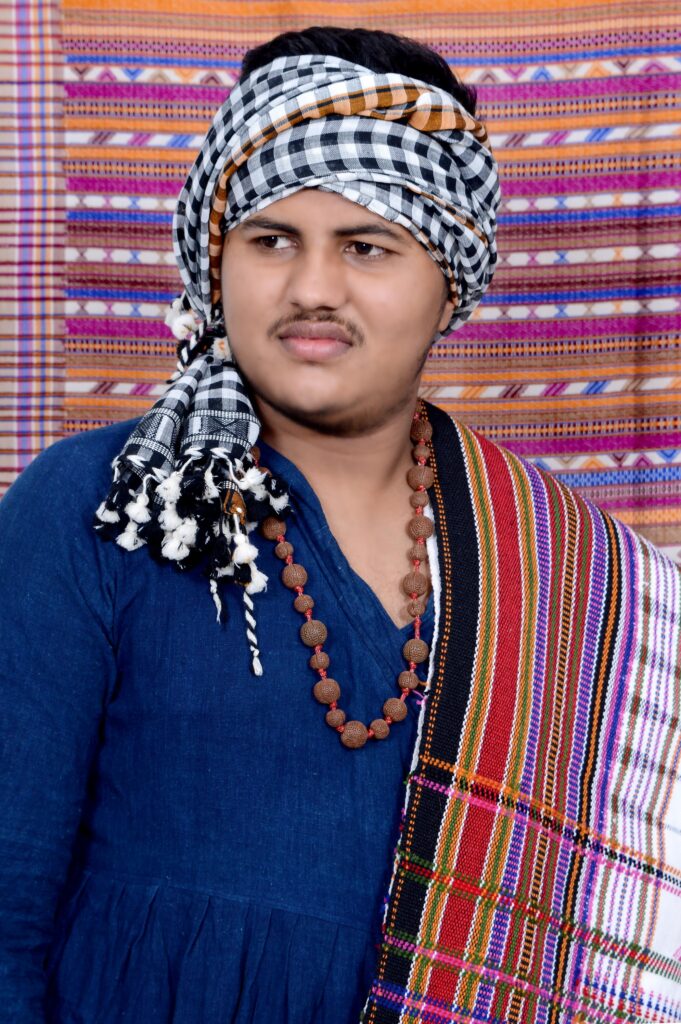

Rajan Vankar

Master Weaver from Kutch, India

Rajan Vankar is a young master weaver in the 4th generation from the rural Kutch region of India. The 21 year old artist is fully dedicated to his craft of traditional Kutch weaving, while sharing the story and culture with the world. “When I was a child, at the age of 10, I had a dream – to introduce my weaving all over the world. In my heart, I dreamed about going abroad, to show my weavings and to present myself, and to represent, maintain and preserve my traditions.” He has been learning and practicing the art of weaving since the age of nine, when his father started to teach him how to weave. In the same year he went to the capital New Delhi for the first time. Travel, work, weaving and family business were all new to him. After a 15 days trip, he came back to the village and started to learn the process. Since then, he has been learning and practicing weaving, dying and how to manage the family business on the side.

“When I was ten, eleven, twelve years old, many visitors were coming to our village and family workshop to view the looms. In my family no one understands or speaks English very well, so I wanted to change that matter. I realized there are some foreign visitors in our workshop and a guide who translated between my father and the visitors. I was watching them and the scene was hurting me, because they did not know what the guide told the visitors.” Rajan taught himself English. It was not included in the curriculum of his regional school, but as he puts it, “If I can speak English, I can tell the truth. I can tell my own stories. I can express my love about my weaving, what we are doing, how we preserve them. Now I have worked with one designer from Japan for two years and I learned a little Japanese. I speak little Russian, little Turkish. And now I’m starting to learn Arabic.”

Many young people choose to not go in their parents’ footsteps and continue the craft traditions. When asked if he at any point had second thoughts about his path as a weaver growing up, he reveals it could also have come differently “That’s the thing; my family never expected that I would pass the exam when I completed my 10th class studies, because I was always working on my weaving and traveling for shows in India. But I passed the exam and my family said that I can continue. One half of me wants to join university, while the other half thought about how I was born in this traditional weaving family.” Rajan decided to go to university to study computer engineering. Two and half years into his studies, 80 percent of his focus was always with the weaving. Thus, he discontinued the computer engineering studies and dedicated himself to the Kutch weaving. “I felt that I was born for weaving and I think weaving has selected me. There are so many people in my community. This is the art practiced by my community, in my village and in my entire region.”

But, Rajan points out, if he would only weave, while nobody knew his work, it would not be enough to keep it up. “I have to maintain the weaving, the dying, telling the story, managing the everyday business and travel to the cities. That makes the artist in a sense, and makes the difference to the others. I feel that the weaving selected me to present my family traditions all over the world.”

Traditional Kutch Weaving

The traditional Kutch weaving is a 600 years old tradition and practiced by Rajan’s family since 150 years. The weaving is done by an extra-weft weaving technique, where a weft yarn is used in the warp of the loom. The weaving with extra weft creates the distinctive designs with geometric patterns. The characteristic, intricately handwoven motifs form the identity of the Kutch weaving. The design and materials have developed and changed with time, but the motives stay the same.

In the 1950s, Rajan’s grandfather was weaving traditional Dahbda blankets. The Rabari community in the Kutch region are cattle herders. They provided sheep wool to the Vankar family and Rajan’s grandfather would in return weave the Dahbda blankets for the Rabari community. At that time, the Dahbda was a much demanded, typical product in the region, and a system of circulation of material and products was in place between the communities. In 1980’s the Vankar family started to make stoles in acrylic wool. In 2000, the big change was Australian merino wool. Since then, the family has innovated their weaving with many types of yarns, such as handspun tussar silk and organic cotton.

Rajan uses primarily handspun fibers such as sheep’s wool, tussar silk and cotton. For the fine merino yarn, the raw wool is imported from Australia to Ludhiana in the Punjab region in northern India, where the mills of the pure fine wool are located. Rajan’s family sources their wool there since four decades. Additionally, he uses local desi wool. The yarns are dyed with natural and azo-free dyes.

Rajan mainly makes shawls and stoles, but also handwoven bedspreads. The desi sheep wool is handspun by his grandmother and older women of the Rabari community. He points out that it requires extraordinary skill and understanding about the yarn and how to spin fiber to thread. Rajan has taken to Instagram to share the process and tradition that goes into the family’s products. In stories and videos he explains each part of Kutch weaving, the symbolic meaning of the motifs, and how the material is treated from spinning and dying to finished shawl.

Creativity and tradition in the design process

Rajan and his father both weave the same motifs, but have developed different styles and different color palettes. Rajan elaborates on his design process. “We think our designs in our mind. Then we create by our heart and we do the design by our hand. We do not use any paper or something like that to weave the design. When I am making a new design, I am fully focused on that. Sometimes I take fifteen days or one month to think about the new design. Because I want to make a marketable design. If I don’t make a marketable design, there’s no meaning for my days. And I take my full time, before I start the weaving.”

The weaving features many intricately handwoven designs. Rajan combines his weaving with needle work and embroidery, with shibori and clamp dye. He says, sometimes a stole takes three days to weave, some pieces take five days or one day to complete. One day is needed to make the tassels at the end of the stole. One day is needed for washing the product in a traditional technique. Then it is pressed and shipped to the client.

Some designs combine weaving and mirror work. The mirror work is done by Rajan’s mother and other women in the surrounding communities. Rajan is working with 20-25 women from nearby villages who make handmade mirror work. After the weaving, the mirrors are placed in tiny spots left open in the fabric. “If I take five days for weaving one stole, the women normally need three days to accomplish the mirror work. It depends on the design. Some shawls take 15 days to complete, others take one month to complete with the entire weaving, mirror work and the finishing by tassels.”

In India, Rajan and his family are exhibiting in New Delhi, Calcutta, Bangalore, Bombay at selected shows. They sell to retailers, sometimes direct to consumer, and take wholesale orders. Rajan also sells direct to costumers internationally and set up his own shop on Etsy.

There is competition from machine-made fabrics, some people try to copy the weaving. But Rajan says, “Some try to copy but they don’t get this kind of look, it is the power of our culture. They can’t match our quality, never. But it is our responsibility to protect our designs, protect our secrets. Some things I keep secret while I am producing my new designs. After one or two years, once they are on the market and many other weavers know about them, I already earn a good income from that design. We create significant textiles which are only made by my family, so we don’t have to worry because no one can make this kind of piece.”

Striving towards excellence in his craftsmanship is part of the role as a master art. “It is my responsibility to take my craft to a higher level, to the next level. To recognize my family and recognize myself in this entire world. And I feel that it is a big thing for me, because I don’t have too many other things or resources. I belong to a small village but I feel proud to have connections. I’m hoping that I am able to travel to Europe or the U.S. next year”.

The next generation of artisans

One aspect threatening traditional craft techniques is cheaper, industrial production. But another issue is that many young people would rather choose other professions than to continue with the work of their parents, go into computer science or marketing, something which might offer less hard work for more pay. Rajan has an advice for the future of young artists of his generation, who are 20 years old and ask themselves if they should commit their life to craft.

“If they continue to practice their craft, their crafts are carried on to the next generation. If they choose the computer or marketing, then they lose the culture and their crafts. Once the craft traditions are lost, nobody can revive them again. That’s my thing: When I was a child, when I was teenager, my weaving connected with me, and today I feel that I was born for weaving, weaving selected me, to play with the weaving, to play with the loom, and express my love about weaving and share it with the entire world. I feel proud that through my weaving, I am able to travel internationally, to work with international designers, to teach people from different countries, to speak to people like you. And today I speak English because for my craft, if I didn’t, my craft and I would not have a chance to meet you.”

To shape a next generation of artisans it not only takes the people, Rajan says, but they have to feel a passion for their crafts and their traditions. “If they only follow the traditions of their ancestors forcefully, things aren’t going to work out. They have to learn from their elders and respect them, and they need to have a creative vision; a creative vision in their mind and heart to make something different from the other artists and the rest of the world, to make the craft and culture more renowned.”

Rajan believes two skills are especially important for the next generation of artisans. “If they learn how to use the computer and to speak English, that will help them to make connections and to generate sales of their crafts, and that will change their lives. Learning those things, I think is the best way to represent and maintain their traditions. I didn’t know the proper grammar, but I speak and people understand. If I have passion for my weaving and a creative vision, then I am able to do all of those things that follow. To do something different than others, it takes time, passion and creative vision.”

Preserving and sharing traditions with a global audience

Rajan Vankar’s childhood vision as a boy in the small village of Sarli has started to come true, and he has already had the opportunity to show his work on an international stage. At 17 years old, his dream of international exposure was becoming reality when was selected for a craft show in Thailand, but since he did not have a passport at the time it had to pass. Last year he was finally selected among the 200 artists from 80 countries to participate in the International Craft Festival in Uzbekistan. “I feel grateful to my ancestors who preserved our weaving traditions. And I am thankful to my father, who taught me about my weaving and guided me when I was a child. I fulfilled one of my dreams and went to Uzbekistan to take part in a very beautiful programme. I learned about other artists and cultures and built new relationships with other communities.”

“I inherited this beautiful tradition of weaving, of colors, designs from my father and my ancestors. Now it’s my responsibility to make a business, to make a good product, to make a good name in this world. And then, to take it forward to the next generation, so that they know that this is the regime from our family, how they have done it in the past.”

Connect with Rajan through Instagram (@rajan_vankar) or visit his Etsy shop.

Interview by Cecilia Palmér.