Technique

Today, there are three primary resist techniques used in Nigeria:

Oniko: this process involves tying raffia around hundreds of individual corn kernels or pebbles to produce small white circles on a blue background. The fabric can also be twisted and tied on itself or folded into stripes.

Alabere: Stitching raffia onto the fabric in a pattern prior to dyeing. The raffia palm is stripped, and the spine sewn into the fabric. After dyeing the raffia is usually ripped out, although some choose to leave it in and let wear and tear on the garment slowly reveal the design.

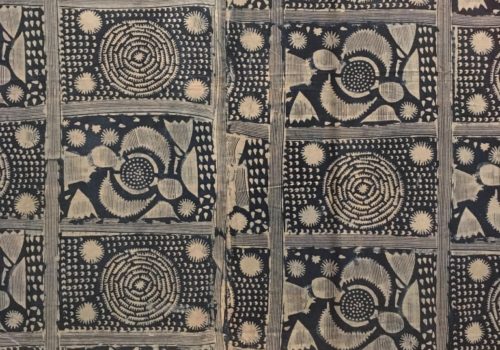

Elecko: Resist dyeing with cassava paste painted onto the fabric. Traditionally done with different size chicken feathers, calabash carved into different designs are also used, in a manner similar to block printing. Since the early twentieth century, metal stencils cut from the sheets of tin that lined tea chests have also been used.

Nigeria is also known for its two-tone indigo resist designs, created by repeat dyeing of cloth painted with cassava root paste to create a deep blue; the paste is then washed out and the cloth dyed a final time. Quality cloth is dyed 25 or more times to create a deep blue-black color before the paste is washed out. Additional forms of indigo resist-dyeing exist in other parts of West Africa; for example, the Bamana of Mali use mud resist, while Senegalese dyers use rice paste rather than cassava root. And the Ndop of Cameroon use both stitch resist and wax resist.

Origin

The tradition of indigo dyeing goes back centuries in West Africa. The earliest known example is a cap from the Dogon kingdom in Mali dating to the 11th century, dyed in the oniko style.[4]

However, by the end of the 1930s the spread of synthetic indigo and caustic soda and an influx of new less skilled entrants caused quality problems and a still-present collapse in demand. Though the more complex and beautiful starch resist designs continued to be produced until the early 1970s, and despite a revival prompted largely by the interest of US Peace Corps workers in the 1960s, never regained their earlier popularity. In the present day, simplified stenciled designs and some better quality oniko and alabere designs are still produced, but local taste favours "kampala" (multi-coloured wax resist cloth, sometimes also known as adire by a few people).